VicForests is aware of false and misleading claims in a recent letter on behalf of 60 organisations – including organisations that have had no interaction with VicForests and no apparent involvement in the management of Victoria’s forests.

VicForests staff and contractors are hard-working, dedicated people working to implement the policies of the Victorian Government. During bushfire events many are at the frontline in protecting the forests and communities from the worst impacts of our fire prone regions.

False claims like these do harm. They impact the mental health and wellbeing of people who have dedicated themselves to the management of forests for future generations. In the case of some of the more extreme claims made in this letter they cause harm to the community by causing unwarranted fear and concern.

VicForests recognises there are different views about native timber harvesting. But it is important that debate is based on facts and evidence.

So, here’s our response.

- Haemorrhaged millions of dollars in public funds

VicForests is a publicly owned company set up to harvest and sell timber from areas of State forest allocated for this purpose. Our business model relies on the sale of timber.

In 2022-23 VicForests had planned to harvest $112 million in timber, returning a margin of $27 million to be applied to the costs of delivering related government services. If we had been able to operate as planned, we would have generated around $500 million in economic activity for the people of Victoria through the sale of value-added products and wages. The only public funding that would have been provided to VicForests was for non-commercial activities to deliver government objectives.

Instead, VicForests harvested $17 million in timber and paid compensation of $110 million for undersupply to customers (compared to $7.5 million in FY22) and $41 million to contractors who were not able to work (compared to $6 million in FY22).

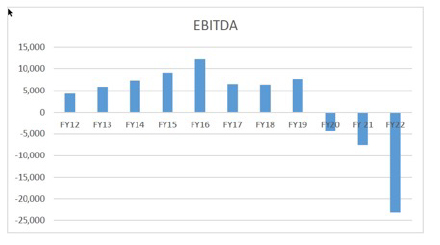

This was entirely due to the impact of orders made in litigation brought by environmental groups – including groups who co-signed the letter. This litigation commenced after the Government announced the decision to cease native timber harvesting from 2030. The impact on VicForests profitability due to litigation is shown in the chart below.

- Broken the law repeatedly, without apology or show of remorse

VicForests is a government agency subject to the ordinary governance obligations and control of other government agencies. It has never been prosecuted by the independent environment regulator.

The system of regulation in Victoria is based on compliance with explicit rules to manage known threats to the environment that have been developed by forestry and environmental experts over many years. These legal rules are developed to balance environmental objectives with economic and social objectives. This balance is required by the Principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development – which is a cornerstone of Australian and International environmental law.

VicForests has repeatedly demonstrated our commitment to meeting, and often exceeding, the explicit rules set by Government.

This is backed up by our latest independent audit result from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action, which saw us achieve an average of 96% compliance across four environment areas: environmental values in State forests, conservation of biodiversity, operational planning and record keeping, and coupe infrastructure for timber harvesting operations. The 96% average compliance findings are a testament to the work our passionate staff undertake in Victoria’s state forests.

In addition, VicForests has been re-certified under the increased new standards of the World’s largest forest certification system – PEFC, or the Australian Responsible Wood standard for Sustainable Forest Management (AS / NZS 4708).

Litigation brought over the last few years was based on arguments that VicForests had a general duty to protect the environment that goes far beyond the balanced rules set by the Victorian Government. The effect of these cases is that VicForests can never know what we need to do to comply with the law, because the rules will now be decided by the Courts – not the Government – on a case-by-case basis. We even had multiple cases brought against us by different environmental groups arguing that different measures were needed to protect the same species in overlapping locations – so that different courts were being asked to rule on new measures at the same time.

There has been no view expressed by the Courts that VicForests would act in any way other than in compliance with any Court orders setting new rules.

3&4. Decimated our iconic native forests which are on the verge of ecological collapse and destroyed the habitat of threatened and endangered wildlife and plants

VicForests works in very small areas of native forest specifically designated for timber harvesting.

These areas have been previously harvested or are bushfire regrowth forests. In a normal year VicForests would harvest about 0.04% of the forests, or four trees in every 10,000.

All harvested areas are re-grown by law with our compliance audited on a regular basis. Suggestions that forests have been “decimated” or “destroyed” have no basis in fact and are untrue.

The areas of highest biodiversity and high-quality habitat are reserved through the Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative (CAR) reserve system and are not available for timber harvesting.

The CAR reserve system protects biodiversity and includes a substantial proportion of public land made up of dedicated reserves and informal reserves.

The areas in which harvesting can occur within production forests are generally lower in biodiversity, or the values are already well protected in the CAR reserve system and through other regulatory processes. In addition to the CAR reserve protections, we undertake comprehensive planning to ensure all operations meet the harvesting and biodiversity requirements under Victoria’s strict environmental regulatory system.

Many of the areas that have been previously harvested have regenerated so well that they have been turned into reserves.

The greatest threat to Australia’s biodiversity is the impact of invasive species, climate change and land clearing. [i] Native timber harvesting which sees the harvest and regrowth of designated areas of forest in 80-year cycles is not land clearing.

- Logged in a way that studies have found increases bushfire risk and severity

Peer reviewed scientific papers found bushfires were not made worse by timber harvesting activities. Studies have found the extent and severity of the 2019–2020 bushfires were a result of years of below average rainfall, extreme fire weather and topography.[ii]

The Panel for the Major Event Review of the 2019–20 bushfires also investigated claims of increased risk of bushfire in harvested forests. They considered that, ‘at the landscape level, neither the nature of the tenure nor the previous timber harvesting history had any significant effect on the severity of the bushfires within these forest ecosystems’.[iii]

- Put the quality and security of Melbourne’s water supply at risk

We have repeatedly debunked false claims that the quality and security of Melbourne’s water supply has been put at risk by past harvesting activities. In fact, inaccurate reporting on the risk to Melbourne’s water supply has been acknowledged by way of an apology from the ABC and in a report by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA).

VicForests’ rigorous planning processes ensure waterways were protected from soil sedimentation caused by erosion. A range of protections (such as stream buffers) were put in place during our harvesting operations for the protection of water quality in accordance with the rigorous regulatory requirements. We also limited harvesting operations on steep slopes.

All timber harvesting and regeneration operations are conducted in line with Victoria’s strict environmental regulations and the State’s Forest Management Zoning Scheme.

- Reduced the amount of carbon stored in forests and released millions of tonnes of emissions

The International Panel on Climate Change has identified that, in the long term, sustainable forest management aimed at maintaining or increasing forest carbon stocks, while producing an annual sustained yield of timber, fibre or energy from the forest, will generate a sustained carbon mitigation benefit.[iv]

Also, a recent report shows that managing a small proportion of Australian forests for multiple uses, including timber production, can provide significant climate benefits when all relevant life cycle factors are considered.[v]

It also found that the rate of carbon sequestration in trees typically decreases with age. For example, in tall dense eucalypt forests the growth rates decrease progressively from around 6.4 tonnes carbon per hectare per year (for 1–10-year-old trees) to around 0.7 tonnes carbon per hectare per year for trees over 100 years old.[vi]

In fact, regenerating and growing forests have the highest rate of carbon sequestration. In mature and older forests this rate decreases as growth slows, and trees begin to decay and die.[vii]

The process of harvesting and regenerating forests for wood products helps store more carbon than a carbon sequestration model that involves no forest harvesting at all. For example, in Victoria, Victorian ash forests conserve an additional 300 tonnes of carbon per hectare when sustainably harvested. This is because wood products retain carbon and harvested forests are regrown.[viii]

An example of this is hardwood flooring from sustainably managed Australian native forests results in a net climate benefit 20 times greater than the use of hardwood flooring sourced from poorly managed tropical forests.[ix]

Another example is the use of hardwood electricity poles instead of concrete or steel is five times better for the climate.[x]

- Failed to regenerate massive areas of the forest estate, leaving the state and Traditional Owners with an enormous on-going land management burden

Over the last decade VicForests has consistently demonstrated that we are meeting our obligations and required standards for successful regeneration.

This is because we plan for regeneration from the start and actively manage it until we meet the standard of the Code.

Following harvesting we regenerate each site with the full suite of eucalypt species that were present prior to harvesting. We specifically regenerate to recreate a natural forest of multiple species that supports a range of biodiversity outcomes.

After the sites are sown, we conduct regeneration surveys to ensure the forests are regrowing. From time-to-time small areas do not regenerate at a first attempt, however we are not released from our responsibilities until all sites meet the regeneration requirements of the Code.

The suggestion that areas that have not yet successfully regenerated are “massive” have no basis in fact and are untrue.

- Spread disingenuous claims about the sustainability of its operations that have had significant impact on regional workers, families, businesses and the community

VicForests is certified under the world’s largest forest certification system – PEFC, branded in Australia as the Australian Responsible Wood standard for Sustainable Forest Management (AS / NZS 4708). To maintain certification, we are regularly audited including surveillance audits every nine months. This is objective evidence of the environmental sustainability of our operations.

If VicForests had been able to operate as planned it would have also been financially sustainable – supporting regional workers, families, businesses, and communities.

- Extended its degradation of forests to some of Australia’s most fragmented landscapes in western Victoria

Operations in Western Victoria are community forestry operations by small and micro businesses with licences to take small amounts of timber from designated areas – mainly for firewood for local communities or fence posts, poles and rails. Some community forestry operations produce sawlogs used in high value products such as furniture and musical instruments.

VicForests supports these businesses by managing the planning and delivery of these activities.

Most of these operations are single tree selection or thinning operations that remove a minor portion of the standing trees and have strict rules about the size of trees that may be taken.

VicForests is also helping with the recovery of the estimated 2300 hectares of forest seriously affected by significant storm events in 2021. In doing this work VicForests is partnering with the Traditional Owners of storm affected areas and also undertaking work on behalf of DEECA.

- Conducted covert surveillance on a Victorian citizen who dared hold them to account

VicForests does not conduct covert surveillance. VicForests does from time to time engage security services to protect foresters and equipment from activists who illegally trespass on our dangerous worksites.

REFERENCES

[i] Murphy H & van Leeuwen S (2021). Australia state of the environment 2021: biodiversity, independent report to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, DOI: 10.26194/ren9-3639

[ii] D.M.J.S. Bowman, G.J Williamson, R.K. Gibson, R.K. et al. (2021), ‘The severity and extent of the Australia 2019–20 Eucalyptus forest fires are not the legacy of forest management’, Nature Ecology & Evolution, Vol. 5, pp 1003–1010, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01464-6

– R. J. Keenan, P. Kanowski, P. J. Baker, C. Brack, T. Bartlett & K. Tolhurst (2021), ‘No evidence that timber harvesting increased the scale or severity of the 2019/20 bushfires in south-eastern Australia’, Australian Forestry, Vol. 84:3, 133-138, https://doi.org/10.1080/00049158.2021.1953741

– D.M.J.S. Bowman, G.J. Williamson, R.K. Gibson, R.K. et al (2022), ‘Reply to: Logging elevated the probability of high-severity fire in the 2019–20 Australian forest fires’, Nature Ecology & Evolution, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01716-z

[iii] Sparkes, GS, Mullett, K & Bartlett, T, 2022, ‘Victorian Regional Forest Agreements: Major Event Review of the 2019–20 bushfires’ https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/vic-rfa-mer-bushfires-report-2022.pdf

[iv]IPCC, 2019, “Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems”. [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)], https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2022/11/SRCCL_Full_Report.pdf

Nabuurs, G.J., O. Masera, K. Andrasko, P. Benitez-Ponce, R. Boer, M. Dutschke, E. Elsiddig, J. Ford-Robertson, P. Frumhoff, T. Karjalainen, O. Krankina, W.A. Kurz, M. Matsumoto, W. Oyhantcabal, N.H. Ravindranath, M.J. Sanz Sanchez, X. Zhang, 2007: Forestry. In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA., https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4-wg3-chapter9-1.pdf

[vi] Ximenes, F (2023). “Forests, Plantations, Wood Products & Australia’s Carbon Balance”, Forests and Wood Products Australia, https://fwpa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Forests-Plantations-Wood-Products-and-Australias-Carbon-Balance-.pdf

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ximenes, F (2023). “Forests, Plantations, Wood Products & Australia’s Carbon Balance”, Forests and Wood Products Australia, https://fwpa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Forests-Plantations-Wood-Products-and-Australias-Carbon-Balance-.pdf

– Montreal Process Implementation Group for Australia and National Forest Inventory Steering Committee, 2018, Australia’s State of the Forests Report 2018, ABARES, Canberra, December. CC BY 4.0. https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/abares/forestsaustralia/documents/sofr_2018/web%20accessible%20pdfs/SOFR_2018_web.pdf

[ix] Deloitte Access Economics (2017). The economic impact of VicForests on the Victorian community, https://www.vicforests.com.au/publications-media/vicforests-reports/economic-reports

[x] Ximenes, F (2023). “Forests, Plantations, Wood Products & Australia’s Carbon Balance”, Forests and Wood Products Australia, https://fwpa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Forests-Plantations-Wood-Products-and-Australias-Carbon-Balance-.pdf

[xi] Ibid.